The DJ and the Gramophone

Needle are the Mediators

November 1, 2005review,

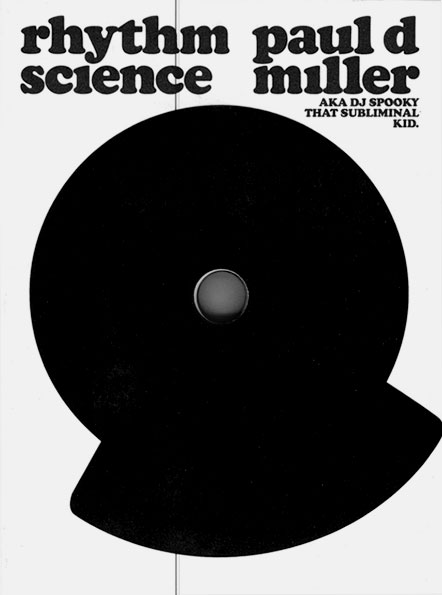

Paul D. Miller aka DJ Spooky that Subliminal Kid, Rhythm Science, Mediawork / The MIT Press, 2004, ISBN 026263287

He is the thinking DJ Paul D. Miller, better known as DJ Spooky that Subliminal Kid, has moved effortlessly for more than ten years between conceptual art, dance music, science fiction and philosophy. Rhythm Science is the long-awaited theoretical analysis of his modus operandi. The book has been designed with considerable care by coma (Cornelia Blatter and Marcel Hermans): at regular intervals the text is interrupted with illustrations and slogans, while the back flap subtly holds in place a mix-CD. Altogether, it is reminiscent of the legendary combined effort by Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore in the 1960s, and presents the text in a similar, light-hearted way as The Medium Is The Massage. That comparison extends beyond the presentation. Spooky, who likes to incorporate a worn McLuhan LP in his DJ sets and talks, frequently resembles the media guru of yesteryear in his writings and ideas.

Like McLuhan in his populist works, Miller has trouble completing his reasoning properly. Both like to use technological jargon and would seem primarily interested in finding an apt one-liner. Miller’s written style is poetic, mixing a post-structuralist preference for multiplicity, networks, heterotopias and data flows with science fiction metaphors and snatches from song texts. Yet for the critical reader there is a problem, since you regularly suspect that Miller has nothing fundamental to say beyond the beautiful words and all too often abruptly cuts short a train of thought. No doubt this is part of the DJ aesthetic of constantly mixing. According to Miller, the needle on the turntable ‘writes’ and ‘recontextualizes’ texts. The DJ rarely uses the beginning and the end of a record and that seems to coincide with Miller’s thinking. His argument is looking for flow, meaning by means of associations rather than strong reasoning. It is a self-assured, associative method, ensuring, for example, that the term ‘rhythm science’ is never explicitly defined and ultimately weakening his more theoretical reflections.

Nevertheless Rhythm Science is a wide-ranging and informative book. The autobiographical component, together with stories from the DJ’s life and in an ongoing, global, almost post-cultural journey, often illustrates better what Miller seeks to convey in his more abstract text. At all events, a DJ was needed who, with a degree of pretentiousness, was to explain what his art entailed beyond the playing of nice records. Spooky also sampled enthusiastically at a theoretical level. In that context, his fascination with nineteenth-century American thinkers, as the precursors of ‘DJ-thinkers’, provides a particularly refreshing angle on the established proponents of ‘Continental thinking’. Ralph Waldo Emerson fits into DJ-thinking on account of his criticism of originality; Walt Whitman on account of his idea of ‘the self’ as multiplicity; W.E.B. Du Bois on account of his conceptualization of a cultural double awareness, and of course Thomas Edison on account of the vital invention of the gramophone. These ideas have gained momentum thanks to sampling and mixing: doing new things with ‘found’ sounds and images, creating new associations, playing with different perceptions of time and memories. The twenty-first century itself is submerged in an ocean of data. When confronted with this intimidating excess of information as to who and what you must be, DJ-thinking supplies an almost indispensable manual to help you take control, as ‘multiplex consciousness’. DJ-ing as a hypermodern variant of psychoanalysis?

The DJ and the gramophone needle become a mediator between technology and consciousness, between the self and fabrications of the outside world. The DJ creates with rhythm science an environment in which people exchange information and can work on new forms, styles and ways of thinking.

When at his best, Miller, with his infectious thoroughly American optimism, imbues you with enthusiasm for the possibilities of, in particular, digital technology as a guide and beacon in an ongoing voyage of discovery in a world with nothing to hold on to. The DJ – and everyone who adheres to his way of thinking – as the hero in the margin, spreading ideas with a view to demolishing rigid divisions of race, class and culture. Rhythm science claims the role of avant-garde, seeking by definition to transcend conservative cultural forces.

Because, despite his training in the populism of hip-hop, Miller emphatically seeks to connect up with the avant-garde of the twentieth century. In the text, his Errata Erratum project features prominently. This remix of Marcel Duchamps’ Sculpture Musical and Erratum Musical is included in the online gallery of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. The collection of cards with instructions for improvised voices that Duchamps continued to collect during his lifetime was remixed by Miller into an audio and video game without end. Errata Erratum is about personal decisions, creating one’s own mix, the choice to identify with a certain sound. Miller does not specify what this all means for the social status of the DJ – until recently an inviolable specialist and trendsetter, a loner who confronts the masses and leads them. In his utopian view the aim would seem to be to resolve this difference between the DJ and the public. Conceivably, if there were to be too many people pursuing DJ-thinking and the DJ were to become democratized as it were, that would also mean the end of the DJ. Or might new hierarchies then inevitably emerge?

In the end, the CD accompanying the book literally clarifies what continues to spook Spooky in his written text. Here he effortlessly mixes hip hop, dub, ambient and electronics with spoken fragments. A pleasing mixture which chiefly acquires added value thanks to such differing voices as Joyce, Artaud, Cummings, Schwitters, Burroughs and Deleuze. As always with Spooky’s music, this is a confrontation with worlds which previously seemed closed off. He disappears into that ‘catchment area’ of meaning and the listener can go looking for connections himself.

Omar Muñoz Cremers is a cultural sociologist and writer. His essays have previously been published in Mediamatic, De Gids, Multitudes and Metropolis M. His first novel is entitled Droomstof (2007). He lives and works in Amsterdam.