Partners

Ydessa Hendeles’s Holocaust Memorial

September 30, 2004review,

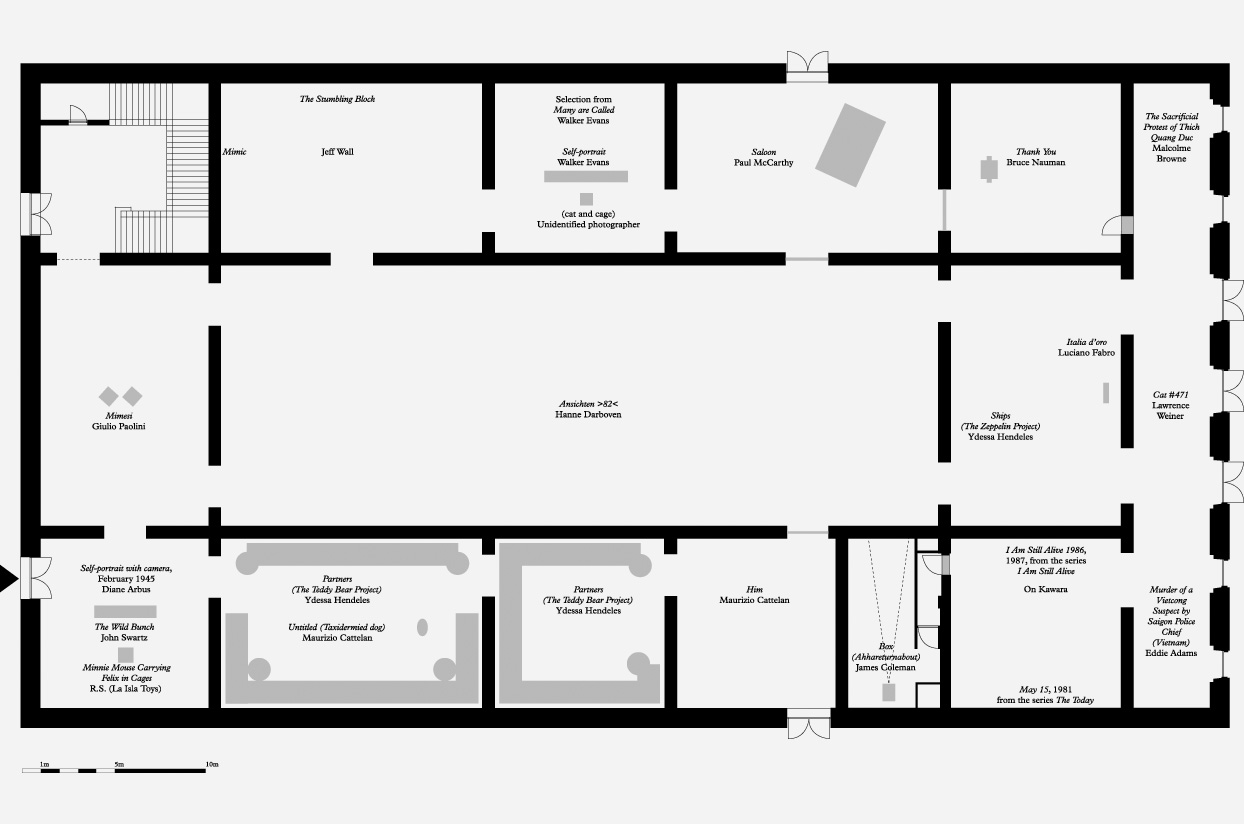

In last year’s exhibition ‘Partners’ at the Haus der Kunst in Munich the Canadian curator and collector Ydessa Hendeles broke the tacit laws of Holocaust memorials. Grouping objects of different natures and placing them in a single context, created all manner of fascinating cross-connections among the objects and with the building, laden by the Nazi past.

The response of an object to contact sufficient to lead to a change in inherent quality (vis inertiae).

La réaction d’un objet au contact suffisant à entrainer un changement de qualité inhérente (vis inertiae).1

What do international contemporary art, popular and historical icons, press photographs, family snapshots, teddy bears and other antique toys have in common? They are collected and presented in continually new configurations in exhibitions by Ydessa Hendeles. Last November the exhibition ‘Partners’2 opened with a selection from the collection at the Haus der Kunst in Munich, which has recently come under Chris Dercon’s directorship.

Hendeles, an internationally renowned Canadian collector and curator, was born in 1948 in Marburg, the only child of two Jewish concentration-camp survivors. In 1950 the family moved to Toronto, where Hendeles ran a gallery from 1980 to 1989 and introduced artists like Jeff Wall, Jana Sterbak and Ken Lum. In 1988 she opened her Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation with the installation Canada by Christian Boltanski: 6000 second-hand pieces of clothing, covering the walls of the room in the former uniform factory.

Amid the modest hype in war exhibitions in the last two years, ‘Partners’ is a breath of fresh air. In contrast to, for instance, ‘No one ever dies there, no one has a head’ in Dortmund in 2002 and ‘Mars. Kunst und Krieg’ in Graz in 2003, ‘Partners’ is not literally about war or its representation in the media and the arts, but rather alludes to it in an indirect and subtle way. Hendeles violates the moral laws that have applied since Auschwitz on the representation of the Holocaust: she does not limit herself to collecting, organizing and testifying; she presents all the parts within a narrative structure, with its own, namely Hendeles’s own, logic.3

The location itself has a startling history, when you realize that the name Haus der Kunst (‘House of Art’) included the adjective ‘Deutschen’ (‘German’) until 1949. The museum, built at Hitler’s orders, opened on 18 July 1937 with the Nazi-sanctioned ‘Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung’ (‘Great German Art Exhibition’), one day before the opening of the ‘Entartete Kunst’ (‘Degenerate Art’) exhibition elsewhere in the city. An ideal location for Hendeles, who had a number of later additions to the architecture removed for the exhibition, so that the building was once more visible in its laden but original form.

The exhibition is divided into three passages, which compel the visitor to walk past the works in a specific order and sometimes to turn back. A small self-portrait of the Jewish-American photographer Diane Arbus from February 1945 opens the show, flanked by a unique studio portrait of the famous Wild Bunch gang, including Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. The third opening object is an antique toy, Minnie Mouse Carrying Felix in Cages, circa 1926–1936. From there Hendeles leads the visitor to her own project, Partners (The Teddy Bear Project), a collection of 3,000 photographs of all imaginable and unimaginable scenes of people with teddy bears: pin-ups, soldiers, children in sailor suits, sports figures, film stars, families.4 All sorted according to the classical art-history method of teddy-bear iconography. Absurd and hilarious, were it not for two dissonant notes: a cuddly sleeping dog by Maurizio Cattelan, which turns out to be stuffed, and several stories of Jewish children whose teddy bears were taken away when they were deported. After the suddenly oppressive quantity of cheerful pictures of teddy bears, the visitor enters an empty room, in which a little boy, seen from behind, kneels in front of a bare wall, also a work by Maurizio Cattelan. It’s a great shock to find that the little boy’s face is that of Hitler. The first passage ends here; the visitor must turn back and look at all he has just seen with new eyes.

Cross-connections

In ‘Partners’, Hendeles applies the rhetorical figure of the synecdoche: using a part to represent the whole and using the whole to represent a part. The portrait of Arbus, for example, refers, in its subject and its date, to the fate of the Jews of Europe, and the studio portrait of the Wild Bunch to the ambiguity of popular icons, but also to the power of images.5 The teddy bear, initially a symbol of comfort and protection, loses its innocence after seeing Hitler, a comforter and protector for a large portion of the German people, after all, and turns once more into the dangerous beast it originally was. Minnie was, along with her partner Mickey Mouse, not only a popular icon in America, but also in Germany, until Hitler outlawed their images. She bears a catalogue number on her cheek – it’s a quick leap to the tattooed numbers on the arms of Hendeles’s parents and other Auschwitz survivors, as well as to Art Spiegelman’s comic-strip version of the Holocaust, Maus, in which cats were Nazis and mice Jews. Except that the mouse now holds the cat prisoner, in an analogy to Hendeles who holds the Germans ‘prisoner’, or a Jew a Nazi. In the accompanying catalogue the endless cross-connections among the works and the world beyond are identified at length, sometimes even to the point of fatigue, by various authors, including Ernst van Alphen, Carol Squiers and Hendeles herself. But Hendeles’s faith in the power of imagination, which can bring these lifeless objects within a greater narrative, shines through the exhibition. It is not the naïve faith of a reclusive collector, but the stinging, confrontational and keen faith of a provocateur.

Typical of Hendeles’s way of collecting and thinking is the inclusion in ‘Partners’ of the world-famous photograph by Eddy Adams of the execution of a Viet Cong suspect. The impact of this one photo on public opinion was enormous: for the first time the American people saw on every newspaper’s front page the cold-blooded murder of an apparently innocent victim by the South Vietnamese general Loan, a great friend of the Americans. The public was shocked; until that moment people had steadfastly believed that only the enemy committed atrocities. The fact that afterwards the suspect did turn out to be guilty of murdering a family, that the ‘spontaneous’ execution was a staged event for a group of photographers and journalists, that Adams himself later regretted having ever taken the photograph, because he had not foreseen its effect and had not wanted it,6 no longer mattered. The photograph ultimately turned the tide of the war and this gave it mythical proportions.

What makes ‘Partners’ so special is that Hendeles does not simply show this icon, but, quite essentially, the photos that came before and after it as well. They restore a context to the photo, allow the viewer to ‘fill in’ the now empty icon with a new meaning and to re-experience the horror of the execution as the series unfolds. And however shocking this may be, Hendeles places the responsibility for interpreting, for being able to interpret pictures once more on the viewer. No ready-made bite-size pieces, no short-lived spectacle, Think, make connections, strip icons bare, think, assign new content, experience and think again.

And along with Bruce Nauman you shout furiously at Hendeles: Thank you! Thank you! Thank you! Thank you!7

1. Lawrence Weiner, Cat. #471, 1980, in the exhibition ‘Partners’.

2. Ydessa Hendeles, ‘Partners’, Haus der Kunst, Munich, 7 November 2003–15 February 2004, exhibition catalogue published by Walther König, Cologne.

3. See in the catalogue Ernst van Alphen, ‘Exhibition as Narrative Work of Art’, pp. 166–186, and by the same author, Schaduw en spel. Herbeleving, historisering en verbeelding van de Holocaust, NAi Publishers, Rotterdam 2004.

4. A selection of 1,500 teddy-bear photos from the collection is included in the three-part publication Hendeles – The Teddy Bear Project, Walther König, Cologne 2004.

5. The portrait stripped the Wild Bunch of their anonymity and led to the eventual capture and death of the gang members.

6. General Loan’s life was devastated as a result, as he was reviled both in Vietnam and in America. And this for something that, in Adams’s words, was only unusual because it was photographed. A comparison with the photos from Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq is obvious.

7. The title of a 1992 work by Bruce Nauman, given by the artist to Hendeles and included in an adapted form as the exhibition’s closing piece.

Brigitte van der Sande is an art historian, independent curator and advisor in the Netherlands. In the nineties Van der Sande started a continuing research into the representation of war in art, resulting in exhibitions like Soft Target. War as a Daily, First-Hand Reality in 2005 as BAK, basis voor actuele kunst in Utrecht and War Zone Amsterdam (2007–2009), as well as many lectures, workshops and essays on the subject within the Netherlands and abroad. In 2013–2014 she curated See You in The Hague at Stroom Den Haag, and co-curated The Last Image, an online archive on the role of informal media on the public image of death for Funeral Museum Tot Zover in Amsterdam. Van der Sande is currently working on a concept for a festival of non-western science fiction, that will take place in 2016.