Jasmin Schädler

As an Artist with a Disability You Almost Always Cause Trouble

April 03, 2018 — 16:55

This is the first of seven blogs by Open! Coop Academy study group Topologies of Touch participants at the Dutch Art Institute (DAI) that reflect on ‘Practising Care’, a day curated on 21 March 2018 by Karen Archey with Mirthe Berentsen, Jesse Darling, Joseph Grigely, Carolyn Lazard and Luke Willis Thompson for Hold Me Now – Feel and Touch in an Unreal World, Studium Generale Rietveld Academie, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam; for the conference, 21–24 March, Archey, Mark Paterson, Rizvana Bradley and Jack Halberstam each curated a discursive and performative programme on how the haptic – relating to or based on touch – is thought and experienced artistically, philosophically, and politically in life, art and theory.

‘As an artist with a disability you almost always cause trouble,’ artist and writer Joseph Grigely said during his talk 21 March 2018 at the Stedelijk for ‘Practising Care’. His talk was titled, ‘Thank You: On What it Means to Care’, expressing how he is often expected to be grateful for unsatisfying conditions because he is deaf, sometimes misspelled (DEATH!!!). He causes trouble just by being there, while he appears to be ‘death’ but is actually deaf yet certainly not dead to interactions.

Causing trouble is the most important aspect of being an artist in any case. Grigely does this with a lot of humour and wit by challenging the topic of care. Taking care should not mean pity or acting conditionally. Taking care is often a job – not only in the medical or day care professions – but as an aspect of every position involving management. It is about enabling and creating agency and not, as it is often misunderstood, about pampering and service. This of course also means the care taker has to open up structures and processes – a painful act that often feels like trouble. When a service is offered without adapting to specific requirements and without engagement, fertile soil for trouble is created. The one receiving care can feel neglected while having to cope with the accusation of ingratitude if this neglect is spoken of. One is always expected to say thank you as the receiver, even if what is offered is not taking the actual needs into consideration. The interaction is avoiding real contact, actual touch, getting in touch with the counterpart. This is how Grigely connected the subtitle of the conference (feel and touch in an unreal world), the topic of ‘Practising Care’ and the DAI study group Topologies of Touch. The question of care versus service and neglect has been an overarching concern quite literally. Grigely helped make sense of it.

Along these lines artist Carolyn Lazard, another speaker at the conference, made an extremely important remark. They observed the missing information about accessibility regarding the conference sharply and without bitterness or accusations. Not being able to provide accessibility is one thing, yet when institutions hold an event on the topic of care and invite guests who work around accessibility more self-reflection is to be expected. The missing accessibility should be pointed out by the institution itself and the event can serve as a point of departure for change. Otherwise the assumption the institutions are only engaging because the topic is trending and opening up access to grants is unavoidably made. A good opportunity to cause trouble.

Causing trouble and distress is something artist Jesse Darling once used to do as they shared with the audience – they were kicked out of Rietveld for taking drugs and earning money on the Internet sex industry at night. They invited conference participants to feel good. ‘You are not the only one with problems’, could summarize the workshop. The task was to talk to your neighbour about marginalisation and illness as well as collaboration and care. But to get into the mood everybody was asked to position their bodies in response to statements according to their approval or disapproval.

I had a happy childhood

I feel safe in the streets

I am physically attractive

I am not racist

I know what I am doing with my life

This is all about showing others how you position yourself, not about an actual opinion. It is picking up on the need to belong to groups yet without reflection. In a time of populism mobilizing bodies to form groups and diabolizing otherness this method is questionable when not contextualized. The care through reflection was missed.

Ines Marita Schärer

Where You Wouldn’t Go, You Want to Go, You Can’t Go

April 03, 2018 — 16:54

I went through the glass door, passed the security guards, walked around the corner, went up some steps, walked along a corridor, snaked through the rows of chairs and sat down on a bench at the side of the room.

Artist Carolyn Lazard asks in their speech: how did people get into this room? Is the space physically accessible for everyone? I remember the many turns and twists I had to do with my body, how many times I had to push and pull a door (a white one, a green one and a red one) and lift my legs to arrive at the white bench in the auditorium.

In the workshop by artist Jesse Darling, we are asked to stand up if able. Darling asks questions and we take a position in the room, if you agree, go to the right, if you don’t agree, go to the left. Or yes on the right, no, on the left. You can position yourself somewhere in between. Is the body in the movement honest? How many bodies follow the crowd to not be exposed? To not stand alone on one side?

In artist Luke Willis Thompson’s performative work, bodies also follow other bodies. A single person follows the performer, who is black. The participants were brought to places they had never been, where they can’t normally go. They were brought to places where they were exposed to danger, to make palpable the danger black people were and are still exposed to.

During Darling’s workshop, a young woman told me about her experience in a work place where she was sexually harrassed by her boss. Her work place was in an area in which she didn’t feel safe. Her body was exposed to violence, yet she wasn’t able to quit having been dependent on her salary.

The places we want to leave: how do we escape places in which the body is exposed and in danger?

The places we want to be: how do we make those places accessible for all sorts of bodies and minds?

I recently encountered a group of deaf people. I regretted that I was not able to speak the same language. Our bodies met; our minds didn’t. In school I remember when the teacher showed us the sign language alphabet. I was fascinated, but I didn’t learn it.

To invite others, we have to leave our zone of comfort. We gain a lot when we invite other bodies, other minds. Artist and writer Joseph Grigely said in his talk: ‘We are equally different in our differences.’

Alejandro Ceron

To Step Out of Our Comfort Zone

April 03, 2018 — 16:53

We arrived in a crowded auditorium inside a high-ceilinged bathtub-shaped intimidating building, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. The audience was mainly composed of Gerrit Rietveld Academie students. It was hard to move or find a place. People squeezed in. I sat in the first row, where I felt quite stiff when Jorinde Seijdel, head of the Studium Generale programme, started the event by welcoming invited guests and audience.

The first speaker to take the stage was New Zealand-based artist Luke Willis Thompson. Presenting three works developed while in residencies in the US and back in New Zealand, Thompson mentioned the #BlackLivesMatter movement and his mixed roots as sources of reflection and inspiration. At the very beginning of his presentation he gave insight into his personal background: his mother, a white woman with Irish roots; his father, a native of the Fiji islands who literally swam to New Zealand. Thompson’s work deals with the idea of being lost, community trauma, the production of identity and terror tourism. One of the presented works was a performance in which the audience followed the performer from the museum to a ghettofied neighbourhood. The work induced thoughts about safe spaces, a claimed illusion people commonly strive for – from individuals, friends and families to institutional bodies.

Following Thompson’s presentation, artist Jesse Darling contributed a loose collaborative intervention addressing potential conflicts related to identity and subjectivity. Darling asked five questions with which the audience had to agree or disagree by positioning themselves on the right or left side of the auditorium. The questions ranged from complex and intimate to seemingly innocuous: did you have a happy childhood? Do you consider yourself to be physically attractive? Do you agree not to be a racist person? It was tricky and puzzling to see how a majority white audience would respond; most identified themselves as not racist. I wonder about the effectiveness of such visual ‘polls’ in times of rising populism.

The second part of the intervention was collaborative. People in the audience arbitrarily paired up to talk to one another about intimate experiences. I left the room. I simply did not feel comfortable. Their intention was to make people feel comfortable about themselves through realising everybody has problems, insecurities and, so to speak, guilty pleasures. The proposed exercise and its form felt intrusive, advancing an uncomfortable awkwardness. If this was precisely their intention, which would be ironic within ‘Practising Care’, their invitation came across as naive, unconscious and rather careless.

Dutch writer Mirthe Berentsen shared her experience of the making of a project inside a mental health institution in the US. During her presentation, ‘The Beauty of Distress’, Berentsen shared a selection of pictures from her residency while speaking about the common language patients in the process of institutionalisation tend to develop, a particular kind of language spoken and understood only within the institution. She explained how patients share their not understanding of the ‘normal’ world. Indeed, who could know how to navigate an unaccessible world of barrier-like conventions?

Artist and activist Carolyn Lazard met the audience via Skype. Quite abruptly, they started their contribution asking the audience to think about who was in the room and how they got there. They continued showing three different video works. The last one was particularly striking. The video showed a frame from above where a person would proceed with the ritual of filling seven boxes with pills, each with the name of a day of the week. The work exposed the weekly routine of a person bound to a heavily medicated treatment in order to have a ‘normal’ life or survive.

‘Thank You: On What it Means to Care’ was the title of artist and writer Joseph Grigely’s presentation, one of the highlights of the event. He delivered a witty and light yet emotive talk on what it means to live deprived of sound. As part of his daily life, his disability permeates his work. However, he noted, his disability is not the only factor that produces his subjectivity.

He talked through the different forms of communication and interactions disable people enable. He explained how being disabled often results in being perceived as a problem, and how causing trouble is in fact a big part of an artists’ work. A few days earlier, in our theory seminar with Marina Vishmidt, we spoke about useful art and the function of art as a can opener, exposing troubles rather than attempting to solve them.

Communicating with disabled people seems troublesome because it demands we step out of our comfort zones. There are challenging requirements when communicating under these particular conditions. ‘It is not only about the willingness to communicate, but about the patience and care needed to overcome a barrier between two people’, said Grigely. There has to be a collective effort to make things accessible and break the barrier unimpaired people often build between them and disabled people. After all, as Grigely noted: we are all going to be disabled at some point, if we live long enough. The comment is an attempt to build a bridge towards empathy, patience and understanding. The procedures of individuation try to isolate and individuate issues that belong to the commons. Individuals then find themselves alone with problems that must be tackled collectively. The commons must be protected and perceived as such for they are the glue that holds us together. Grigely noted how we are all different in our differences. Nobody is more different than anybody else.

Other subjects touched upon were the political charge of aesthetics or the paralinguistic language of exchange. Karen Archey, curator of ‘Practising Care’ closed a roundtable discussion with the question of how to call out institutions that often contribute – with their structures, architectures, languages and rituals – to the making of a less accessible world. Indeed, we are not all living in the same world.

Aldo Ramos

Awakening Our Relation With Disability

April 03, 2018 — 16:53

I will limit my comments to those most relevant to me, that keep moving my thoughts on care, the topic of this conference day.

New York-based artist Carolyn Lazard approached the audience via Skype, a projection on the big screen. It was weird to see this format in such a big lecture. We could see her, but she couldn’t see us. That was not a problem; she knew exactly what she wanted to say.

To introduce this subject she used a video in which lots of pills are organised in boxes to be consumed over the course of the week. She pointed to the problems that healthcare and disability bring in relation to the institutions that host the supposed facilities.

I was not aware of these problematics, as they were something I have never experienced. Until I invited my cousin to visit my world, the places I go, what I like to do. My cousin became dependent on a wheelchair because of a bullet that hit his spine during a robbery. I realised that most of the places I visit are inaccessible to him, and now also not for me. I’m amazed that I never realised such an important detail. I am convinced that these details are only the tip of the iceberg in terms of collective thinking or collective ignorance.

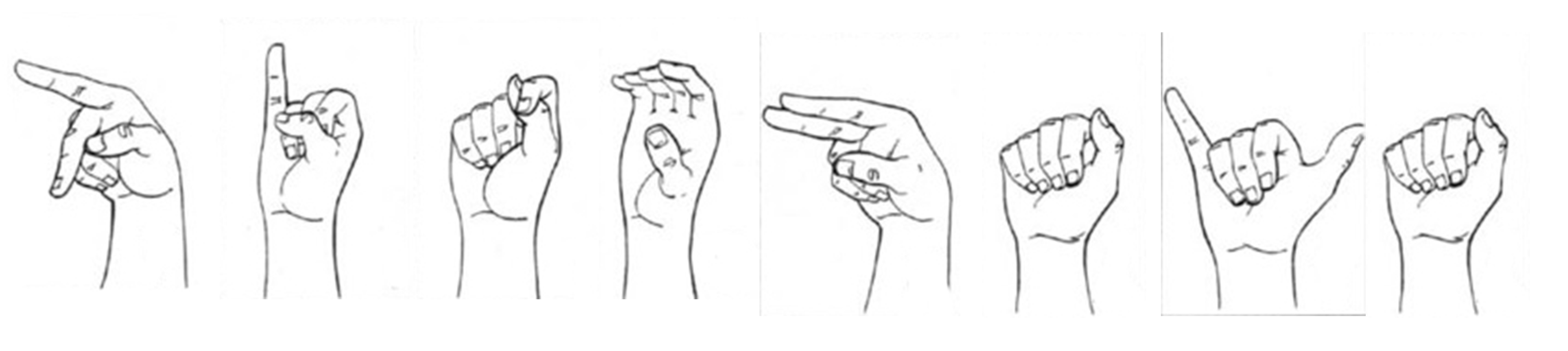

At the front of the stage were two sign-language interpreters. It was interesting to see how efficient this way of communication is; it is possible to express so much in gestures and movements. Sometimes I could feel the energy of the story more through the interpreter than the speaker. We all gesture while speaking; does this use a different part of the brain than spoken language? Through gesture can we communicate what we don’t say or want to say?

The interpreters translated Chicago-based writer and aritst Joseph Grigely, whose presence took over the room as soon as he stood up. His speech is full of energy and emotion, the control of the volume of his voice is perfect. Way better than other speakers. His pronunciation is a bit difficult to follow but clear enough to understand. Even though he has been deaf since he was a child, he learned to speak perfectly.

His story awoke my attention towards our relation to ‘disability’. He spoke about how a ramp for disability should go both ways, not only for using a wheelchair but for everybody. My first thought was that the interpreters are not here for him, but for us. They made possible our interaction with him. They became a bridge that is built not for him, but for us, a ramp not for my cousin but for us. A bridge is meaningful only if it goes both ways.

Anja Khersonska

Gerrit Rietveld Academie Student Fashion

April 03, 2018 — 16:52

S T R E E T style // Gerrit Rietveld Academie students at //

Rietveld Uncut : hold me now : conference_day1 : Practising Care

There is a question repeatedly being asked: who is in the room?

How do you dress if you want to go to a museum? How do you dress if you want to be an art student?

I approached several students who especially caught my attention during the smoking break.

Who do you meet in the smoking break? Is fashion a form of care for the body? What does coolness mean in a conversation about the warmth of skin? Do clothes only keep us warm?

Mónica Lacerda

Notes on Practising Care

April 03, 2018 — 16:51

Institutions, galleries and other groups in the cultural field can be intricate webs, often difficult to navigate if one lacks the right tools. ‘Practising Care’ co-curator Karen Archey invited the audience to think about the role of such organisations and to reflect on their limits – budget, physical ability, geographical space, et cetera – while rethinking the urgency to foster care within such constraints.

Those who depend on care to live or to be able to work have been marginalized even in the art field, despite its reputation for breaking with normativity. From where I stand, it is clear that Western society – shaped by and for capitalist, colonial, white, able-bodied, middle- and upper-class cisgendered men – continuously subjects all others to being less or unworthy. What does receiving and giving care mean in the art field, taking into account that the art world is, like other more traditional contexts, pierced through by the same norms it apparently refuses? How can the needs of each participant be taken into consideration?

Archey invited us to think about the influence of empathy on our relationships, as well as the need for individuals to feel that we can trust one another. Without bearing the weight of this interdependence, we can focus on the potentiality of this connection. The question that stayed with me is: how does one practise care in an institutional context and within the art sphere? My answer: an ethics of care asks for intersectional feminist practices:

- Daily interactions that take place within the institution opposed to underlying these intimidating spaces, bridging theory and practice;

- The potential for confrontation to unsettle the position of the institution, opening a space for discussion by resisting its fixed norms;

- Refusing the ableist nature of the art industry and reflecting upon what it could mean to disrupt the social norms of productivity;

- Be mindful of cognitive and neuro divergences that often are invisible and contribute to marginalisation;

- To work for the common good and towards communal care, practising self-care as a means to open up space for communal care;

- Workshopping what a safe space could mean, working towards inclusivity, allowing all subjectivities involved to have agency;

- Actively working on communication as well as on accessibility;

- Empathy and healing as holistic tools with which to work in and for the community, in solidarity and friendship.

Pitchaya Ngamcharoen

There Are Many Ways of Listening

April 03, 2018 — 16:48

Touch addresses issues of race, gender, class, and ability; productive confrontation where the privileged are forced to listen.

– Karen Archey, introduction to ‘Practising Care’, 21 March 2018

There are many ways to listen, not only through the ears, but also through tasting, smelling, touching and seeing.

The interpreters for deaf artist and writer Joseph Grigely, one of the speakers at Studium Generale, sat next to Karen Archey during her introduction quoted above. Grigely was not introduced, at least not to the majority of the audience.

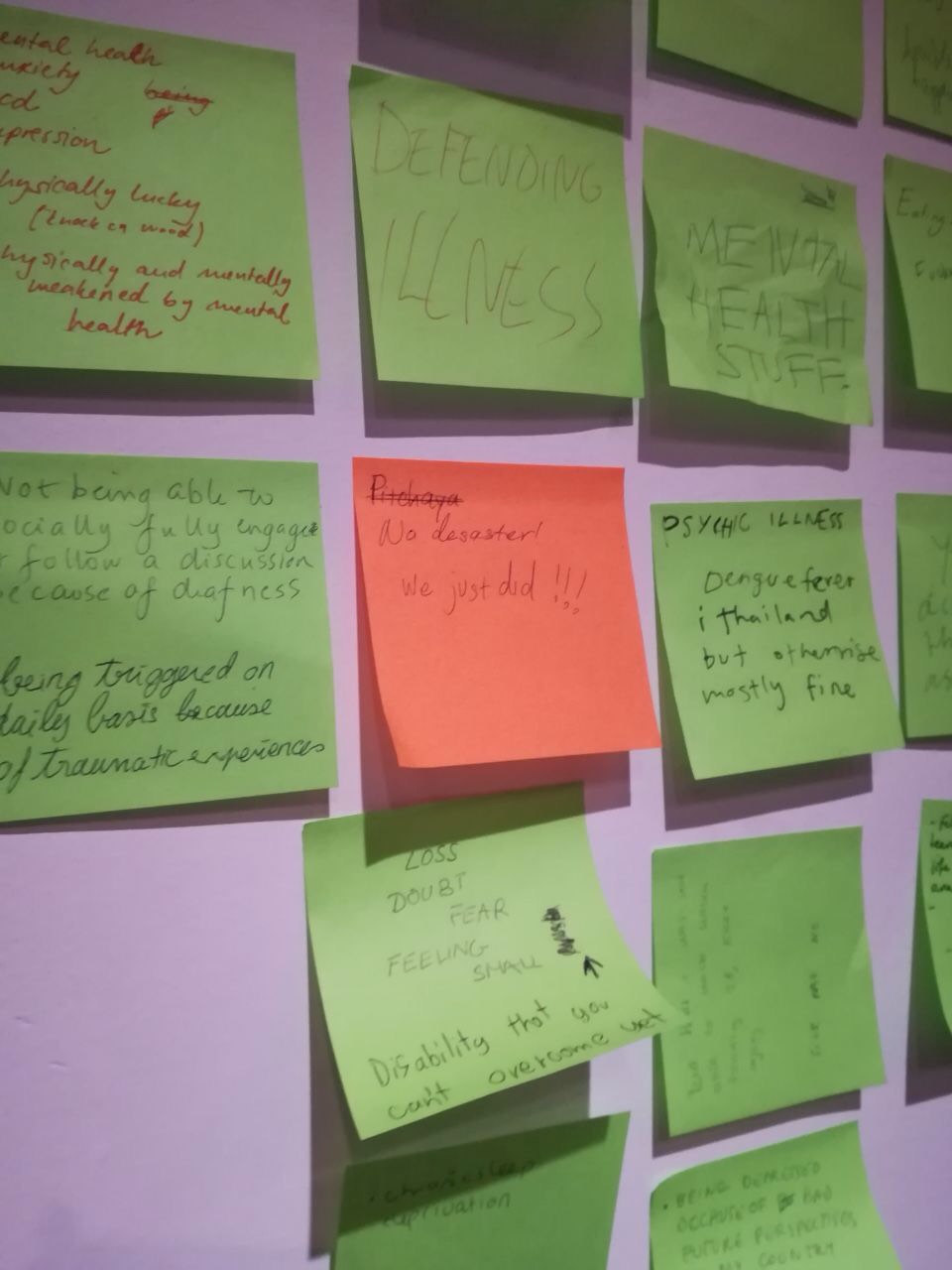

During the conference I participated in an activity presented by artist Jesse Darling. The artist asked us to pair up with someone nearby to engage in a dialogue. We wrote our thoughts on Post-its, each colour representing a different question addressed, and then stuck these to a wall with others of the same colour.

Fortunately, I was sitting next to a gentle man who was listening through an interpreter.

P: My name is...

Interpreter:

P: What’s your name?

J: T h o m s o m e.

P: Sorry?

J: Thomson.

Interpreter: Joseph

P: So which question shall we start talking about?

J, P: Hmm.

J: These are such difficult questions! We have to work so hard on this.

P: We can do it! What about this one, the experience of marginalization? What does it mean actually?

J: It means a social process that pushes a small group of people outside or out from the centre, to make them the underclass. I feel it of course, sometimes I feel completely outside when other people are talking.

P: I think maybe it’s something that everybody at some point feels. Right? Even though you are not being pushed outside, you might have that feeling anyway as we always seek to be in a place where we feel we belong.

What about this question, experience of illness and disability? I’m sure you don’t have much to say…

J: Hahahahahaha. I think the most difficult thing for me is the invisibility of the disability. If people don’t see it immediately then they assume that you hear everything. There was one time that the police came to me because they were telling me I could not do something but I didn’t hear it so I kept doing what I was doing but it was not permitted.

P: Oh yeah. For me also the invisibility. I have dealt with some depression. As you face it by yourself, nobody else notices it unless you speak out. Mental illness can be so underestimated and unnoticed. You know? Actually, now in this activity people with colour blindness might have difficulty accessing it because colour plays a role in it.

J: Yeah, let’s play with that! Let’s put our paper on the wall as if we don’t see colours. Shall we do that?

As Joseph began: ‘The public presence of the artist is to bring your art to the public, to bring your disability into the public eye.’ That’s why sometimes it’s difficult for others to accept.

David Maroto

The Future Is a Reservoir of Absolute Indeterminacy

June 24, 2017 — 10:41

‘Pricing Time: Remarks on the Ontology of Finance’ is a public seminar by Beirut-based philosopher Ray Brassier, moderated by Dutch Art Institute (DAI) core tutor Bassam El Baroni that took place at the DAI, 23 June 2017

The seminar’s abstract reads:

Suhail Malik’s 2014 paper, ‘The Ontology of Finance’, challenges orthodox Marxian accounts of the connection between capitalism, finance and politics. Drawing on Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler’s Capital as Power: A Study of Order and Creorder (2009), Malik argues that capital accumulation is not propelled by self-valorizing value but by the differential logic of pricing. In his words, ‘administered prices make explicit that price is the medium of capital accumulation qua power-ordering’. In finance capital, price becomes an abstract variable independent of its origin in concrete assets: it is no longer a measure of value, only of itself. Thus, Malik argues, financialization is not a species of capitalization; rather, capitalization is a species of financialization. Since the logic of pricing involves a binding of time, it is through pricing as time-binding that capital exerts social power. But capital’s time-binding power cannot be challenged by resorting to extant models of political action: collective human agency does not offer a credible counter-power against the power-ordering exerted by pricing. Since derivatives markets are the medium of pricing, the suggestion seems to be that financial speculation is the proper medium in which to countermand capitalism’s power. This seminar examines the key moves in Malik’s argument and critically appraises its political ramifications.

Seven o’clock, I’m sitting with my laptop ready to type out my observations of the seminar. I’ve been asked by the Dutch Art Institute (DAI) to record my impressions of the event in real time on this blog. In other words, the text that follows is a sort of stream of consciousness: I listen, see and write, without much mediation between the stimulus (the names, ideas and arguments discussed in front of me) and the response (the thoughts, memories, references and images evoked). As I’ve never done this before I have no idea which direction this will take, but hope it results in an enjoyable experience, both for me and for you, dear reader.

We’re in a theatre in Arnhem that is a sort of multi-purpose black box. Ray is sitting at a table right in front of me. As is common for these kinds of presentations, the screen of his laptop is projected onto a larger screen behind him. But it is just a simple Word file without images. The set up is very simple, like the structure of the evening. After Ray’s lecture, Bassam will moderate the conversation between him and the audience.

Gabriëlle Schleijpen, Head of Program at DAI, takes the floor to introduce the speaker and announce the contents of the upcoming DAI week – the last this academic year. Excitement courses through the audience, which is mainly comprised of students. She mentions me and my association with the DAI through my PhD project. What a Russian-doll effect, I’m writing her words speaking about me writing her words. She also speaks about Bassam, who is nearing the completion of his own PhD. Unlike in the UK, where both Bassam and I study, the artist PhD is a very new thing in the Netherlands, so it’s really up to each academy to define what such a trajectory means in their respective academic contexts.

‘Central to Ray’s writing is nihilism’, Bassam says when he takes over the floor from Gabriëlle. ‘Nihilism is not the negation of truth, but rather the truth of negation.’ Ray listens in the background to how Bassam speaks about him, how his work has influenced Bassam’s PhD research. ‘A derivative (this definition will come in handy today) is a contract between two parties which defines conditions’, Bassam says. ‘Suhail Malik's essay says that derivative markets suppose a medium of pricing.’

I’ve met Suhail a couple of times: once during another seminar here at the DAI. The second was at a lecture he gave at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. At the latter, and the subsequent conversation we had over a drink following, I realized we read the same philosopher, George Dickie. ‘Not a very sexy choice’, certainly not as much as the omnipresent (in the art world, that is) French post-structuralists. I also realized, judging by the reaction of those who listened to Suhail’s arguments, that Dickie’s definition of the art world, the mere proposition that such an ‘informal institution’ exists, and how it functions, causes much unrest in certain people: those most interested in keeping the art world’s status quo.

But I’m moving away from the point of this blog.

Bassam finishes, it’s Ray’s turn. ‘I’ll try to reconstruct Malik’s paper, arguments for thirty minutes, an extraordinarily important paper. Then I’ll offer some critical observations’, Ray says, taking off his glasses in order to read from the laptop’s screen. Ray quotes Suhail’s essay: ‘Derivative markets present a systemic risk to national and world economies. The relative size of these markets is a fundamental risk to geopolitical as well as economic security.’

According to Suhail’s argument, financial speculation perverts the very definition of social institutions – all the way to nation-states. Capitalization is a species of financialization, not the other way round. Speculative capitalism does not obey any rational determination, not of any social order. Ray is breaking down and translating Suhail’s text for us, and I’m selecting and translating Ray’s talk for the reader of this blog. At this point I fear that my specific academic and professional background will betray the fact that much of the lexicon employed by Ray is quite alien to me.

‘This paper is a real tour-de-force. My own stand is of someone who thinks that Marxist accounts should not be rejected so quickly. I’m skeptical of Nitzan and Bichler’s proposal. If you jettison Marx’s theory so quickly you end up with a provocative but also problematic political proposal. Capital accummulation is at once and necessarily a political fact’, he says, quoting Suhail quoting Nitzan and Bichler. ‘As Malik puts it, price tells us how much a capitalist would be prepared to pay now to receive a flow of money later. The logic of pricing is independent of the logic of any local economy. The ability to price is the ability to control a whole social system. Businesses are not just unproductive but, moreover, necessarily counterproductive – as are capitalist societies overall and in general. Price fixing sets the market.’

I turn to look back and see that most of the students, pens in hand, are directing their eyes to their own notebooks, not computers, just regular notebooks, that is. They are noting down what they are listening to. I am also listening and writing, the difference is that they have the freedom to scribble loose notes that will remain private, so their not making sense afterwards is of no consequence. I’m enjoying this blogging (as said, it’s my first time). However, I cannot help but secretly envy the students for their writing freedom. Mine is subjected to public scrutiny.

‘Derivatives are an interpersonal and subjectively constituted reckoning on circumstances external to the wager itself, predicated upon the non-knowledge of the future.’ Ray continues unravelling Suhail’s essay. ‘This is complicated: what’s going on in derivative pricing is not that you have two different prices, it does not involve the exchange between two different prices, because the two prices are not actually determined quantities. If you simply have a difference between two differences. Malik claims that the differenciation that constitutes the difference between two terms, A and B, involves both terms. It involves a reference to A and B, it’s a temporalization because you’re deferring the determination of the value of the difference.’ He’s explaining Derrida now. We’re still at the explanatory phase, he hasn’t begun his critique of Suhail yet.

He talks of gambling and coin tossing. A given series of throws divides time and space into discrete units. It’s a metaphor for the volatily of the market and its endogenous condition to the movement of pricing. ‘Derivate pricing and volatility are constructions of time, it’s the difference between the present future and the future present.’ With a contract you’re creating a future that conditions your own fabrication. Stock market, speculation, unpredictability, it reminds me of a movie, π (1998), the only film by Darren Aronofsky that I actually like, his first one, the one he made without economical means but with good ideas.

‘Actualization is not the actualization of a previously existing probability’, Ray says. He gets more and more excited by his own train of thought. His body position has changed, his shirt unbuttoned by one button and his face flushed. His glass of water remains untouched. ‘It’s time to conclude.’ He recapitulates the four stages of Suhail’s argument: Nitzan and Bichler on capital power; logic of derivatives pricing as variant of Derridean différance; Elena Esposito on time-binding; and Elie Ayache on thetic contingency. ‘The practice of pricing transforms social institutions relation to their future. This is supposed to be emancipating by abjuring any system of prediction and control.’

Ray hasn’t looked at his screen for a while, he looks down, searching for the right words. This is the moment of conclusions. ‘We must find ways to cope with indeterminacy. The claim is that any attempt to control indeterminacy will result in authoritarianism. The future is a reservoir of absolute indeterminacy. Okay, I think I’ve been speaking long enough.’

‘Yeah’, the lady next to me says.

‘So I will stop.’ The audience applauds. Bassam walks on stage and breaks the ice with the first question, hoping that others will follow. He reads a question from the notes he has been taking during the talk.

‘Contingency is uncalculable. Chance is calculable’, Ray replies. ‘Contingency is ontological: everything that is could have been otherwise. It’s not contingent because something else could have been. That is completely undeterminable, not constrained by anything that is. This is the reason why markets are unpredictable, because they are inscribed in radical contingency.’

Bassam attempts to link everything that has been said with artistic practice. Not a bad idea, considering that this lecture takes place in the framework of an MFA programme. Ray rejects inscribing artistic creativity as contingent, he thinks it would then be theological, an imitation derived from god’s act of creation. Some in the audience giggle. On the other hand, at risk of contradicting what he has just stated, he adds that, although this account is anti-humanist, it presupposes a material practice, a peculiar social practice that has the power to make and unmake social institutions, precisely because it’s done by human beings. Trading is a game played by humans. This reference to games makes sense to me, as the game is a set of rules that manifests itself through the actions of the subjects who play it. I always thought that, while playing, subjects aren’t free anymore, but subjected to the rules of the game.

Ray speaks emphasising the h in ‘while’. ‘However complicated a practice is, it’s still going to be complicated by other social practices.’ My neighbour to the right nods with an audible grunt.

A member of the audience asks about risk and prediction. ‘What is real is undetermination as such, efectuated by the pricing process. That’s why pricing makes the real, makes and unmakes the world, our social institutions’, Ray answers.

Bassam asks a question that triggers Ray to speak about games again, pricing as a game of exceptional status. Anything can be priced. The notion that the cosmos is a game (this idea is so evocative!), the throw of the dice (Nietzsche, Derrida). It seems to him a mistake to ontologize games in this way. ‘Human beings are supreme gamers, if you want. Who can participate in a game? That’s not a trivial question.’

One more student comments on games, it seems to be a preferred notion among the audience. Ray says that each throw of the dice is independent of other throws, hence the discrete segmentation of time. Every move is absolute in itself, there’s no memory of other previous moves. And it’s true, games have no history, they are not accumulative. On the stock market, whether you did good or badly in the past, it won’t affect your behaviour in a contingent way.

We’re over two hours now, way more than the ninety minutes estimated. Ray keeps talking of roulette and factoring in every possible variable, which is exactly what Suhail rejects. There’s nothing that you can know that would help you to wager better the next time.

Bassam puts an end to the discussion, promising that remaining questions by the audience can be put to Ray over the next three days, because he’s staying at DAI, invited as an external examiner for the students’ graduation presentations.

Everyone applauds, it’s the end.

Agata Cieslak

Carl Andre as a Site

May 22, 2017 — 23:13

This blog entry covers Curating Positions: ‘Second Order Observation’, a Skype meeting with DAI students Sonia Kazovsky, larose, Helen Zeru and Floris Visser, and Van Abbemuseum representatives Steven ten Thije, Charles Esche and Annie Fletcher, along with Emily Pethick from The Showroom

Conversation transcript:

(Please note, this transcript was made on the spot and is an edited version of my reading of the key points)

20:02 Emily Pethick is on Skype.

20:02 Floris invites everyone to drink wine.

20:03 Question of organizing the meeting; Ilan (a DAI student attending the meeting) suggests starting; Sonia prefers waiting a bit more for more people to come.

20:04 Waiting...

20:05 Charles – Emily’s son – appears at the meeting (virtually, on Skype). Annie Fletcher decides they start.

20:06 The meeting begins with a general ‘thank you’.

20:07 Short introduction by DAI students.

20:08 larose sums up the process of making the project: It all started in February 2017 at the Van Abbemuseum. We all organized the settings, groups in relation to the caucus and the idea of this year’s theme ‘becoming more’. Some words stuck with us in terms of becoming more, like feminist, equal... we decided to think about the statement made by the Van Abbe in relation to work of Carl Andre, which has been exhibited next to the Guerrilla Girls’ work. We were thinking how Andre’s work can be understood in the context of domestic violence – his personal history, etc.

20:10 Sonia asks about what becoming more means for the Van Abbe as an example of a museum. She discusses Andre’s work in relation to museum policy and the autonomy of the work. She also brings up the use of his work in relation to the museum’s collection and how it can be a side context (international position). She asks Annie and Charles how they would try to present these issues to the audience.

20:13 Charles responds to Sonia: Being in the museum should be a constant learning process, where people are coming there to use it. It’s good to remember that this work has been shown in a very specific context (it’s worth mentioning that it is no longer on show) – the first exhibition in Europe building on Nato countries’ citizenry, and Andre belonged in it. We thought it was very interesting to recreate that. We focused on that, not on his personal history. Also Lee Lozano’s works changed the position of his works. There was always the excuse put forward that Andre was not guilty. If the verdict would be different, maybe the placement of that work within the show would be more problematic. We have to remember also that we are interested in the position of visitors – we think about how the visitors respond to the exhibition, so here we are on the same page as you. There is also a question of ownership – we are not the owners of the collection (the goverment is), so we have a limited response, although there is a lot that can be held in our hands. It’s good to keep all the crimes in the past.

20:18 Sonia: We also researched how you can bring a new context to the work. You are about to update your policy. With the new policy the museum can claim more political agency (not necessarily a negative thing).

20:20 Annie: We had this interesting conversation on ideas of reacting to works, like performance and activism, etc. Constituency. Our conversation went to Ana Mendieta’s protest at the Tate. And it is exactly the idea of use that the visibility of the work within the collection can bring another set of meanings to. Removing it from the collection also destroys those possibilities – not only in relation to the work, but also to the language by which the work has been mediated.

20:23 Sonia quotes: ‘When destructive analytical techniques are undertaken, a complete record of the material analysed, the outcome of the analysis and the resulting research, including publications, should become a part of the permanent record of the object.’ If we talk about the changing times, and how research can actually apply to work, it can be useful. It’s not about the judgment of the museum if Andre had been found guilty.

20:24 larose: The point was to stop showing it in the first place, because circulating it redistributes the values of the conversation around the work back to the public.

20:25 Sonia: What would it change to bring the work back onto the market? How to sabotage the value? In a place where we consider ethics as a value, how can we discredit the value of work?

20:26 Isabelle (DAI student): The autonomy of the work exists in the collection but also outside of it.

20:27 Steven: My interest in addressing this work went also to ethical questions. We represented the public museum and public body, and with the decision that Andre is not guilty, it is hard to not exhibit this work just because of an ethical dilemma. Also if not shown in the Van Abbe it would go to another collection. What I struggle with, is that if you look at the room it has been displayed in, Lozano is the only female artist with work in it. If you highlight only the problems in this particular work (of Andre), the other problems might disappear.

20:30 Charles: There was also the incredible idea that there were gaps within the collection. There were a lot of complaints as to how we could refill those gaps. This question was absurd. Of course there will be gaps. The gaps are just a given. If you want to fill the gaps you have to ‘buy the world’.

20:31 Annie: They (the gaps) have been also very violent...

20:31 Charles: Absolutely, but that’s why we decided to not fill the gaps, as it’s not possible, just deal with the history. But also if you look at the collection: if at any time there was a possibility to choose between men or women, men were chosen. So I decided to buy some women’s artwork, as it didn’t look like a gap, but complete gender imbalance and a determination of prominence.

20:33 Floris: In a sense we are responding to this art historical linearity to make it a bit more inclusive. If you want to include Andre in a collection and the display then you should also include the different aspects of the story. In that way you can make it de-modernized.

20:35 Annie: I think it’s interesting. One can create contexts and use them. It doesn’t mean that we won’t show Picasso in a white cube...

20:35 Charles: Not in a white cube... please...

20:35 [Some part missing by Annie]

20:36 Sonia: There are (within the collection) a lot of other artists too, that also should be in jail...

20:37 larose: How do you as a feminist museum create a safe space for your users?

20:37 Anie: You’re right (...)

20:37 Sonia: So how can we proceed?

20:37 Charles: There are many ways. We could buy a work of Ana Mendieta and show it instead of Andre, but we could also show it (an Andre work) in context, like an archival context, etc.

20:38 Isabelle: Does filling up gaps create gaps on the other side?

20:38 Charles: We could attach the context in a website, etc. The thing is, we cannot choose our successes. The work has to be shown in certain ways. So showing that work in that way, it would always be in a context of the archive. When we were thinking of showing Hitler’s collection – that wouldn’t be possible in an art museum, but in a historical museum (Hitler was a ‘bad boy’, etc). With Andre we can't do that. What we could do, is to start to address Mendieta as an artist as well.

20:41 Sonia: We could also ask the question, what is the power of the museum and what are the limits of this kind of Institution?

20:41 Annie: Within our networks of the museum you can try to push limits.

20:42 Floris: We were talking about consensus as well.

20:42 Charles: Just to clarify: the consensus is not between us, but between us and our predecessors.

20:42 Floris: There are always the ideas that exist in certain timeframes, but they can be changed.

20:43 Charles: To be fair we have done a lot of that. We copied Sol LeWitt’s work and gave it away for free. I can’t agree with the judgment that this museum is set up in terms of a "Western" (Charles air quotes) way of thinking of the museum as an institution.

20:44 Floris: What we are trying to break is the "Western" historical narrative, and recreate that.

20:44 Charles: We don’t have the responsibilities of the future.

20:45 [Some text missing by Ilan]

20:45 Annie: Reactions might be stronger for something that varies.

20:45 Steven: If we bring the work into the collection, we burn its capital because it can’t be re-sold; while if it’s still on the market, it’s gaining value. I’m not sure, if I find the market value of Andre’s work the most interesting thing here. More so, the meaning of his work in relation to his personal story, but also to the easiness of its reproduction – the only way you know that this is original is because you have a certificate. I don’t think the use of the copy in the exhibition would be visible to the viewer (just a set of metal plates). Re-enactment of work ... is not about copying the artwork, it’s about copying the idea. If you think about Andre’s work, you should add the awareness of the situation to the work – to have the possibility to either show the original, or the copy. It’s up to any future user to decide. But, the decision has to be made and indicated (on wall label). In a sense, all the subjectivity of this work is not about the subjectivity of the work, as it’s very reproducible. The man making these kinds of objects, and at the same time using his name to sign them – it’s very much in a macho style.

20:51 Sonia quoting: ‘Museums should ensure that the information they present in displays and exhibitions is well-founded, accurate and gives appropriate consideration to represented groups or beliefs.’

In that case there is an ability to attach something to the work, attach it to the document of its orginality.

20:51 Steven: This is doable.

20:51 Sonia: We did talk to lawyers and we found ‘Art and Finance’ institutions; they say that it’s possible. We need access the archives of Van Abbemuseum.

20:52 Annie: What do you aim at, to have access to the archive or to destroy the work?

20:52 Sonia: Not to destroy, but to attach something to the file of the work.

20:53 larose: Or the option would be to maybe show Mendieta instead of Andre...

20:53 Sonia: This is also up to you as an institution.

20:53 Charles: We are open to you. We, of course have to respond to the ethical problems, but also remember not to damage the work, it has to be possible to exhibit it in the future. So we could attach the document to the archive files or curate a new context of the exhibition; or also maybe buy some Mendieta (if we could afford it – yes, we could) works. I would be against the idea of marking the work of Andre. I would be completely against that, especially because I’m not an owner of that work.

20:55 larose: We never suggested destroying it. I was just wondering; it could sit well within the context of the caucus.

20:55 Annie: I think that’s great. It was problematic for us, when I thought that it’s connected with the destruction or a removal of a work, but I’m open to the idea you are suggesting.

20:56 Sonia: We of course, have different voices within the group; there are many ideas. I’m interested particularly in attaching the document to the archive, so this research co-exists and co-circulates with the work and the certificate.

20:57 Charles: Absolutely, we also have to remember the autonomy of the work and what it means for the work to be autonomous. That’s something we already researched within previous projects and we are completely on the same page here. The question is, what kind of techniques can we use? It would be maybe nice to exhibit the work based on its archives.

20:59 Sonia: Also the fact that we are in Eindhoven, facing domestic violence.

20:59 [Some comments from Annie on domestic violence missing]

20:59 Charles, to larose in relation to safe space: How would it work in this context?

21.00 larose: I can’t answer that now. It depends. It would have to also bring the visibility of women, also women of colour to the exhibition. There are many aspects of that context, we would have to think deeper on that topic.

21:00 Sonia asks Emily to add something.

21:01 Emily: It’s hard to follow, sometimes I couldn’t hear. I think the proposal to show the work in a different context is good, as it brings a new social context too. This becomes a part of a history of the work. If the group proposes to go ahead with this research, there are a lot of questions that can be asked. Like Charles said, to not show this work and make Andre guilty would be so much easier. I think to do further research before the next step wold be very important here.

21:02 Annie to Sonia: You also spoke with Zach [Blas], and Sven [Lütticken]...

21:02 Sonia: Zach was already very tired after the presentations; we asked advice from Marina [Vishmidt], Rachel [O’Reilly] and Sven (the theory teachers at DAI), with whom we had an e-mail exchange – he contributed to the idea, gave us some suggestions and also gave us a list of other murderers, pedophiles, etc., which are being exhibited in the Van Abbe.

20:05 Annie: Maybe it would be good to have a show of those people?

20:06 Charles: We can put the list of names on the wall...

21:06 Sonia: Again it’s not about the individual, but about which role the museum takes in this relation.

21:07 Charles: It would be nice to organize something related to home-violence.

21:07 Sonia: That’s right, we could bring up some proposals, etc. We are committed to this conversation.

21:08 Charles: Yes, please send some. We are open for propositions from you. The museum doesn’t want to take the political action.

21:08 larose: But then you initiated this caucus?

21:08 Sonia: Yes, the museum is taking a political stand.

21:09 [Some part missing by Charles]

21:10 Sonia: To a certain degree it’s very important for the institution to take a political stand.

21:10 Annie: I wouldn’t trust it also if only we would decide. I could decide that Anselm Kiefer was a fascist. Also we are a public institution, we have to understand its nature and the responsibilities.

21:12 Sonia: I completely understand, but to a certain point there is a limit, to which the public institution should take a stand.

21:12 Annie: Of course, that’s why we decided now to go on (with your suggestions) as we treat them seriously.

21:13 Charles: We can’t see the blind spots ourselves, that’s why we need help from the outside too.

21:13 Annie: Thank you, let’s figure out how to go on.

21:14 Charles: Yes, that would be nice if you could come with some proposals.

21:14 Sonia: Yes, of course.

21:14 Charles: Thank you for blogging.

21:14 Annie: Charles, did you actually just say that?

Agata Cieslak

Summing up from a Distance

May 21, 2017 — 18:30

In this short summary of yesterday’s talks and presentations I try to outline the key thoughts and themes

Day two of the symposium was split up into three panels on the notion of the future. Each presenter focused on different visions of speculative theories, futurisms, futurologies and accelerationist manifestoes in relation to capitalism, nature and labour.

PANEL 1: THE LABOUR OF THE FUTURE, THE FUTURE AFTER LABOUR

Talk by McKenzie Wark:

post-humanism, nature, ecology, time, accelerationism

The only way to think about the future is to be post-human. McKenzie Wark discussed the relationship between human and nature introduced through the accelerationist manifesto. He brought up the concept of geological time and speculated on humans’ function within this idea of time: what would it mean for biological processes – would capitalism stop destroying natural sources of planet Earth? He argued there is no such a thing as ecology, which only means a ‘self-correcting system’, and that we should think beyond it as nature isn’t homeostatic.

Talk by Maurizio Lazzarato:

future visions, progress, technical machine, social machine, production, productivity

In his talk, Maurizio Lazzarato focused on the relation between the future and progress. He started with modernism as the template for progress in our society. He spoke about how First World War destroyed and put a halt to the visionary ideas and progress of Twentieth Century. He also described the two wars as the failure of civilization. To the idea of time as progress, he opposed the feminist apporach to thinking the present, rather than trying to speculate on the future. In specific, he refers to a text by Carla Lonzi, Let’s Speak on Hegel, in which Lonzi addreses the failure of Hegelian dialectic and of Marxism to analyse certain social dynamics that make capitalistic accumulation possible. He reminded us of the term general intellect used by Karl Marx, which appeals to production and productivity and its dependence not on the time of work, but on the development of technology and social cooperation.

PANEL 2: SPECULATIVE PRACTICES

Panel moderated by Sven Lütticken with interventions prepared by Diedrich Diederichsen and Marina Vishmidt. Speculation was introduced here as a tool different from and accompanying critique.

Talk by Diedrich Diederichsen:

dream, utopia, responsibility, passive-active, shamanism

Diedrich Diederichsen introduced the dream as a passive medium to construct ideas. The dream is not only an abstract concept, where thoughts can develop, but also a tool for shaping future realities. He mentioned terms like hope and utopia in relation to the dream, but also marked the fact that to dream is simultaneously to be responsible. He contemplated the notions of passive reception in relation to active production and tried to prove that both have the same values in relation to shaping the future. He referred feminine dreaming and the idea of the dreamer being a performer of a certain kind of magic that could be compared to shamanistic practices. He discussed the meaning of dreams in relation to media, to history (and how they looked before the invention of the cinema) and indicated that the dreams will be forever present, that this kind of passivism is the future.

Talk by Marina Vishmidt:

art and value, labour, speculation, fear, history, resilience, fantasy

Marina Vishmidt’s talk was based on questions of time, history and ownership of the future. She reminded us that the concept of the future cannot be separated from labour and value, which refer, of course, to capitalism. Vishmidt brought up the concepts of dominance and resilience and discussed the question of the power of speculation. She asked some questions about reality and the idea of its being reproduced or speculative. An important note in her talk was also a fragment about fear: the fear of the future is at the same time a fear of history, she said. The talk was accompanied by examples of artworks as speculative fantasies for reinventing the future.

PANEL 3: SOCIALIST AND AFRO FUTURES (on film):

This panel redirected the focus away from Western visions of the future to East Germany and the work of Gottfirend Kolditz and Joachim Hellwig.

Talk by Doreen Mende (accompanied by the film Staub der Sterne by Gottfried Kolditz):

Doreen Mende began her talk by screening a short fragment of Eastern-German sci-fi film Staub der Sterne. The film follows the adventures of Capitan Suko after crashing his spaceship on planet TEM 4 in responding to a distress call. The captain, who with his crew is invited to a party by the planet’s leader, senses the invitation is dishonest (it turns out it’s a guise to kill them and wipe their memories and ultimately enslave them) and refuses to attend. Mende drew attention to the fact that Staub der Sterne, a cinematic movie from the 1970s, was not only a pop culture vision of the future, but also a political tool for constructing reality. She pointed out that fantasies of the future in popular culture differ based on their respective political and social situations. She also mapped the production of future-fiction in Soviet countries, and explained the means of this production in propaganda.

Talk by Kodwo Eshun (accompanied by documentary Schwarze Stern by Joachim Hellwig):

Schwarze Stern, a documentary by Joachim Hellwig looks into Ghana’s five years of independence under President Kwame Nkruma. During Nkruma’s presidency, the country modelled its socio-economical systems on socialist patterns. The country tried to cooperate with the Eastern Bloc, resulting in, among other things, the production of a new propaganda language. Schwarze Stern documents the processes of introducing new visions of postcolonial future to the society. During his talk, Kodwo Eshun tried to explain the meaning of futurism and speculation in postcolonial countries, where capitalism was implied as a and associated with danger and enslavement.